Virginia Eifert, Nature Writer Extraordinaire

November 27, 2021

Virginia Eifert, nature writer extraordinaire

[feature story Illinois Times July 21, 1978]

“We need to drink at the source, to know the wild places, to learn their truths . . .”

By John E. Hallwas

“We followed a narrow lane through autumn woods where fallen leaves and remnants of last summer’s smells made a nostalgic perfume,

like memories of delicious foods in an old kitchen. We had entered the quiet world of autumn.”

So wrote Virginia S. Eifert of Springfield, Illinois in a 1963 issue of the Living Museum, a publication of the Illinois State Museum, enticing thousands of readers in Illinois and other states to experience outdoor pleasures for themselves as she re-created her own adventure down a woodland path. By that time, she had become one of the great nature writers of the Midwest.

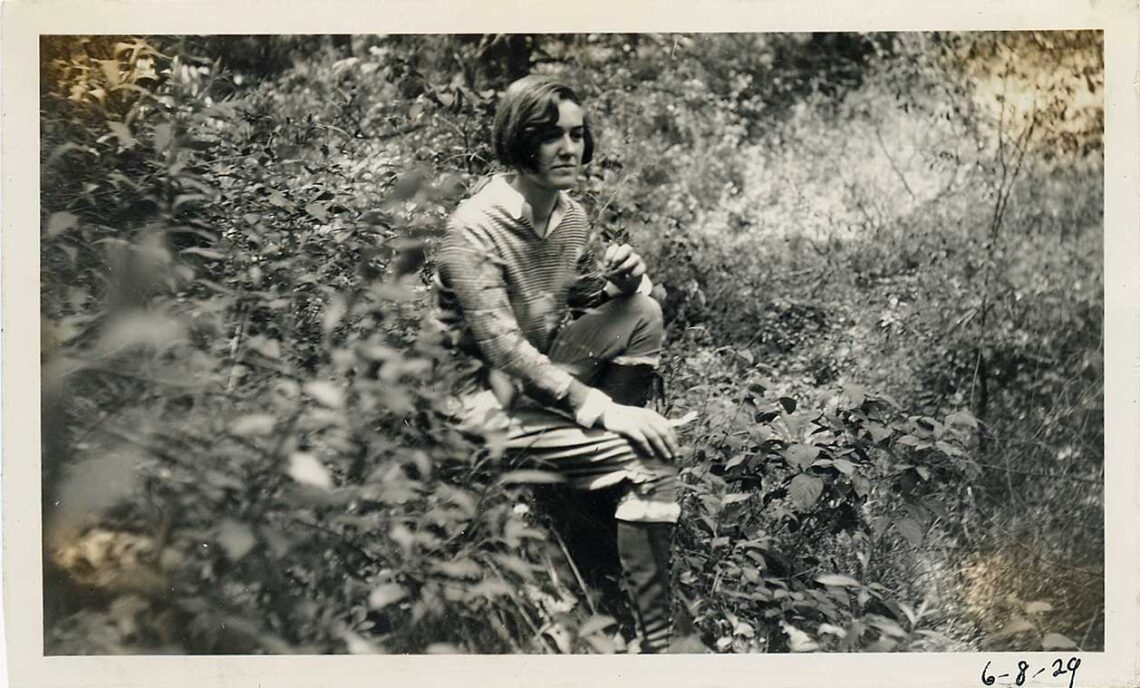

She was born on January 23, 1911, at 810 South Park Avenue in Springfield, Illinois, the oldest child of Ernest and Felicie Snider. Her mother had a lively interest in nature and often took Virginia – and later her brother Melville and sister Ernestine – outdoors on picnics and excursions. According to her sister, Virginia “practically grew up in Washington Park,” and a number of family photographs support that comment.

Her dad, Ernest, showing Virginia the pond at Washington Park. 1916.

Even as a youngster Virginia had an enormous love for wild things. During her teenage years she was sometimes up and outdoors before dawn to hear the birds, and more than once she came home drenched because she refused to let a summer rain interrupt her observations in the park. She also took very seriously the job of feeding and protecting the birds near her home, and, like many children, she sometimes brought home “pets”: frogs, toads, snakes, turtles, a lizard and even a bat.

During her high school years, Virginia was a fine student whose main interests were nature study, writing and art.

Early in 1928, her senior year, something happened that curtailed much of her activity and completely separated Virginia from contact with the outdoors for several months. She contracted an illness that made her dangerously weak. It was probably rheumatic fever, although not accurately diagnosed at the time. As a result, she was confined to her room for rest, and her world of plants and animals was limited to what she could see from her bedroom window. For that reason, Virginia – who would later earn a national reputation as a naturalist and author – never finished high school. The time of confinement may actually have accelerated her learning, however, for the number of library books on nature that she read during that period was enormous. Writing and drawing helped to fill the long hours of physical inactivity. She slowly regained her strength, but the disease left her with a legacy of heart damage that eventually shortened her life.

The year following her illness saw the production of her first “book.” It is a sketchbook filled with writings and watercolor paintings, titled 1919. A Year out of Doors, and it was sent as a Christmas gift to her grandmother and her aunt, who lived in California. [Virginia was 8]

The most important piece of writing in the sketchbook is a story-like essay called “Summer and the Little Lake,” which reveals a great deal about both Virginia’s love for nature and her writing ability. The subtle theme of the sketch is her own inexhaustible curiosity about life outdoors. Concerning the lake, she says:

“I have skirted its edge, over hills and through the swelter of the marsh. I have seen it in early morning when the dawn mists were yet lingering. I have looked upon its face in the moonlight in June.”

And though she has seen a vast number of birds and plants during those visits, she remarks,

“It is the lake that sees things that I would give much to see, things that happen in the marsh and in the willows that surround it, and the strange things that happen there at night.”

Until 1930, Virginia’s writing was a private matter, but the situation changed when she was invited to write a nature column for the Illinois State Journal of Springfield. The opportunity came about through her acquaince with the editor, J.Emil Smith, who was her neighbor. Her first nature column appeared in 1930, and it was followed by scores of others. [she was just 19]

Typically, she provided seasonal notes on plants and animals in the Springfield vicinity or recounted her own experiences with wildlife. Titles of individual columns included “The Christmas Start,” “The Laws of Nature,” “Indian Arrowheads,” “Wilde Goose Chase,” “My Clam, Annie.”

While she was writing the newspaper column – for which she was not paid – Virginia also began to publish her own weekly mimeographed paper, called The Nature News, which sold for five cents a copy to anyone in Springfield who wanted “up to the minute news on what’s happening outdoors” – as she liked to advertise it. She wrote both the Journal column and The Nature News until the mid-1930’s.

During that period Virginia not only often went to Washington Park, but made trips to the Springfield cemeteries, Lake Springfield, Sugar Creek and the swampwoods along the Sangamon River. She often took guidebooks with her to help identify unfamiliar plants and animals. She also began to expand her knowledge of wild areas elsewhere in Illinois and adjoining states, usually by traveling with her brother Melville in his Model T. Fortunately she recorded some of her experiences in other sketchbooks produced for relatives. One in particular, which carries the auspicious title Peripatetic Perigrinations of 1932, is especially interesting, for it contains a pictorial record of her travels with Melville to such places as Galena, Baldwin Beach at Havana and Turkey Run State Park in Indiana.

It was also during the early 1930s that she received her last formal education. For one semester, in the 1933 – 1934 school year, Virginia attended Eastern Illinois University as a special student, taking courses in botany and zoology. Not only did her lack of a high school diploma prevent her from enrolling in a degree program, but she had little or no interest in a wide variety of subjects. There is some indication that even advanced coursework in biology would not have been to her liking, for she evidently did not care for the rigorously scientific (non humanistic, non artistic) approach to nature.

During the 1930s, Virginia was deeply involved with the Springfield Nature League (which later became the Springfield Audubon Society). When the monthly Nature League bulletin, a mimeographed publication, was launched in January, 1938, Virginia was a contributing editor. An article called Spring Song in the February, 1938 issue contains this passage:

Mice whistled comically; chickadees piped spring soon and hung upside down on the elm twigs. Blue jays chortled and gurgled; They gathered in flocks and flew whooping through the woods as the urgent calling of the thaw brought with it the intoxicating knowledge of spring. Brilliant cardinals sang from the tops of the highest trees, and down in the rugged, winter bleached horse weeds rose the jingling’s and twitterings of juncos, tree sparrows, and goldfinches, who picked up seeds softened by the thaw.

The Nature League had an unanticipated result for Virginia, for there she met a young man who shared many of her interests and eventually, her life as well. Herman Eifert was a college student when they met in 1934, but he would later become a teacher of biology, physiology and english at Glenwood high school in Chatham and Feitshans High School in Springfield [and later Education Curator at the Illinois State Museum] – and so his professional interests coincided with Virginia’s. Perhaps the most unusual expression of the Eifert’s joint interest in the Illinois outdoors was their wedding ceremony itself – performed atop Starved Rock at sunrise on September 29th, 1936.

Virginia’s first article for a Natural History magazine appeared the month after she was married: “The Tumblebug Rolls the World,” 1/2 page essay in the October, 1936 issue of Nature Notes. With that brief article she began to extend her following beyond the limits of Springfield. Many such essays appeared during the next quarter of a century – on everything from diatoms to orchids – in periodicals like Audubon magazine, Nature magazine, Natural History and Canadian Nature.

But the big break in Virginia’s career was not her successful venture into writing for nature magazines or her column for the newspaper. It was an unexpected opportunity to edit a journal devoted to the subject she liked best and knew most about, the natural world in Illinois. In 1938, Governor Henry Horner informed the new director of the Illinois State museum, Thorne Deuel that he was interested in building a new structure to replace the crowded quarters on the 5th floor of the Centennial Building – but that was a project that would depend upon increased support from the people of Illinois. One of the most productive of Deuel’s ideas for generating that support turned out to be hiring Virginia Eifert to edit a monthly publication devoted to the interests of the Illinois State museum. It was called the living museum.

Aside from achieving its intended purpose of publicizing the museum (the circulation reached more than 25,000 under Virginia’s editorship), the Living Museum provided an ideal outlet for the talents of its editor-author-illustrator. Virginia was essentially free for 27 years to write the kinds of essays she wanted to write. Many of her very best writing is within the pages of the 326 issues that she produced, and those essays provide a remarkable record of her interests and development after 1939.

The earliest essays were short and sometimes end by referring to exhibits in the museum, but Virginia gradually moved away from that format towards lyrical essays that recreated the sights, sounds and smells of the outdoors. One sketch, called the quiet night, displays the descriptive intensity towards which she was moving:

“Now in the West the sky is still a deep indigo green, shading down to the horizon in a last clear lemon light against which shut the far-off silhouettes of trees. A night heron beats slowly across the last bit of glow, is gone, and out in the pasture a late field Sparrow trills a song . . .”

“Now the tree crickets, hidden among the Elm leaves, take up a refrain, their rhythmic, pulsating, jingling sound. these spasmatic sizzling of grasshoppers and other hidden insects breaks from the grass; the crackle of a beetle’s footsteps is loud. A pleasant, slightly damp, warm aroma of evening rises from the cloverfields.”

In the same year she wrote a beautiful prose sketch titled The Winter Rock, based on an excursion to Starved Rock. In spite of her familiarity with the location, it was a voyage of discovery, for the midwinter landscape possess its own vivid details:

Now that sky has cleared to a brilliant, clear blue that shines in contrast to the white world, and up against the color sale white gulls, like moths, on black tipped, immovable wings. An eagle comes flying over the rock, passes it, soars over the river and the forest to the South. The blueberry bush with ends that spangle from the rocks and are brilliant in the snow; their red twigs and little coral buds gleam in a blur of color. A chickadee hangs upside down on the witch hazel bush, the seed capsules are empty now. A downy woodpecker trumps loudly in the silence.

Edgar Lee Masters read that essay in his hotel room in New York City and was inspired to write a poem based on it called “Starved Rock and Winter.” Masters had discovered Virginia’s Living Museum essays while he was in central Illinois gathering information for The Sangamon (1942), and he dropped in to see Deuel at that time and commented that Virginia’s sketches were “word pictures and prose poems.” [Master letter to Virginia here]

Later in her career, Virginia’s desire to share her joy in nature led her to develop what probably has to be called a philosophy of nature perception. She always encouraged others to cultivate their senses more fully, to learn to see, hear, smell and touch with more complete appreciation. The result of such experiences makes for a richer life for each individual. For Virginia herself, with her incredibly heightened perception of the natural world, the most dazzling experiences occurred when she “stepped for a moment inside the enchanted circle of the wild” – when she could see and hear those activities that are not often a part of human experience.

[Below: a full issue of the Living Museum, every month of every year for 326 issues]

But aside from the endless variety and great sense of fulfillment to be found in nature perception, there is also the thrill of new meaning – meaning that can be gathered by anyone who gives close attention to the outdoor world, regardless of where and how it is encountered. In “To See the Year,” an essay from 1961, she says:

“To see the year is to adventure into deep truths laid freely open not only to philosopher and scientist but to any one of us on his way home from work, or out fishing, or gardening for simply looking from the window, or laying a hand against a tree trunk, or examining with new vision the wonder of a snail, a stone, a star.”

The general subject that always excited the most impressive writing from Virginia was night time. “The Quiet Night” is a fine descriptive piece. “November Moon” is just as effective in its sensitive evocation of a landscape at night:

“It is November and the moon puts a dead-white brilliance upon hill and lake, makes the frost more tangible, makes the approach of winter more assured. Behind the black branches of bare trees, the stars glitter, and the tripods of a locust tree, for no reason at all, bet a sudden sharp tattoo that is loud in the silence.”

Another essay, “Silence Listening to Silence,” captures the strange beauty of the Aurora borealis – “An airy flaring, a dim, green white light wave wavering across the north, drifting in tenuous veils, dissolving into nothingness.”

A vast number of excursions into the outdoors at night – in Springfield, at nearby New Salem State Park, in the Northwoods, and at the clearing in Door County, Wisconsin – lay behind these superb night pieces. As Virginia says at the close of “The World of Darkness,” an essay that describes night perception, “Night is a special world of blossoming, of hunting, of living, of dying the world whose door closes gently with the coming of the sun.”

Original art from “Birds in Your Backyard”. Well over 100 of these watercolor and ink paintings are in this book.

Early essays for the Living Museum soon led to longer works. First, she wrote several paperback guide books for the museum: Birds in Your Backyard (1941), illustrated with her own drawings; The Story of Illinois (1943) and five others. Though not her best writing – limited as she was by the guidebook format – those works often display a descriptive intensity that is rare in Natural History publications. For example, the opening of her brief discussion of the timber wolf in Illinois Mammals vividly recreates perhaps the most common human experience of that vanished personification of wilderness:

“It was a cold night with brilliant stars in the black sky, and at the edge of the forest the wolves were howling. It was an eerie, frightening sound, alone smooth lullooooo – and then, abruptly, it changed. The voices broke into a dog-like barking – bark and howl, bark and howl – and off they went on their swift feet into the glistening winter darkness.”

Illustrated by one of the greatest American painters of the 20th century, Thomas Hart Benton.

The guidebooks increased Virginia’s desire to produce full length books. In the early 1940s she worked on the manuscript for a botany book, which she illustrated with her own drawings, but it was turned down by several publishers and never appeared, and so it turned out that her first book was not on Natural History at all. Like many Springfield residents over the years, Virginia was fascinated by Abraham Lincoln, and she often visited the reconstructed village of New Salem just south of Petersburg. It was from these experiences that her first book developed, a historical novel about Lincoln’s flatboat trip down the Sangamon, Illinois and Mississippi Rivers. Written for adults but rejected by several publishers, Three Rivers South (1953) was later rewritten for young readers and accepted by Dodd, Mead and Company [New York], which subsequently published another 15 of her books. Virginia’s interest in Lincoln eventually resulted in four more volumes. Virginia was always planning two or three books while finishing whatever she was currently writing, and in the 1940s and 1950s she gathered information for two volumes on the Mississippi River, Mississippi Calling (1957) and River World (1959).

Meanwhile, she needed more firsthand knowledge of the Mississippi River and the country that it traveled through, and so she sought and received permission from the J.D. Streett Company of St. Louis to ride their towboats, the Cape Zepher the Saint Louis Zepher. Just as Mark Twain found the romance of the Mississippi reflected in the river boats of his era, Virginia came to regard modern towboats in a similar way, as indicated by an essay in the Living Museum of 1950:

“Long, quiet, aloof, the towboat moves rapidly down the channel of the big river. The mellow whistle has all the mournful and exciting cadence of a foghorn on the ocean . . . wistfully, wishfully, the eyes of those on the muddy shore, on the green levy, or on the tall white cliffs, follow the towboat and its tremendous barges.”

Two books grew directly out of Virginia’s personal contact with the natural world: “Land of the Snowshoe Hare” 1960 and “Journeys in Green Places” 1963.

For Virginia, the flora and fauna of the northern Wisconsin country where her family spent several summers provided distinctive and delightful experiences. The rabbits and meadow mice, pine forests and cranberry bogs that she observed are recorded in the Land of the Snowshoe Hare, and what is certainly her most lyrical prose outside of the Living Museum essays. Even the forest mushrooms are described in all their “elaborate, gaudy, impossible, gnomish forms and colors.”

Her conviction about the re-recreated value of the northern wilderness is expressed in more personal terms in a poem that was apparently written during the same period. It was found among Virginia’s papers after she died and was published in the Living Museum. It is entitled and undated and contains the following lines:

When city noise and city stress

Conspire to wreck my happiness,

When television, cars and noise

Usurp the place of forest joys,

Then to my heart comes memories

Of lakes and bogs and quiet trees.

I listen, and again I hear

The cries of wild geese drawing near.

I listen, and my heart’s deep core

Noise of lake waves lapping on a shore

The gentle sounds of leaves at night,

The awakening of flowers to light.

…..

And so I mortgage city stress,

Anticipating wilderness

Journeys in Green Places was inspired by a different set of circumstances. In 1935 the noted Chicago landscape architect Jens Jensen acquired 135 acres of woodland in Door County, Wisconsin, near the tiny town of Ellison Bay. Soon afterwards, he built there a stone lodge, a school building and two dormitories – establishing a nonprofit adult school in the woods, which he called The Clearing. He believed that contact with wild places was essential to mental well-being.

Virginia’s association with The Clearing began in 1957 when noted author, explorer and naturalist Rutherford Platt was invited to teach there (his brother had a cabin nearby). He agreed to come if Virginia Eifert would come as well, for he lived in the East and was not as familiar as she with Midwestern flora and fauna. Platt himself invited Virginia to be a guest naturalist. She agreed, and in May, 1957, she began a relationship with The Clearing that lasted for the rest of her life. Each year she taught at least two weeklong nature classes – commonly in May and September – and was the best known and best loved instructor there.

Class members rising at dawn often found Virginia already waiting for them outside the sleeping quarters. Likewise, long after dark, she would walk with a group down to the Meadow just to sit to identify the night sounds or point out the constellations.

In the 1960’s, when the American people were first being made aware of the multifaceted environmental crisis, she was one of the voices calling for public attention to the problem. She did not live long enough, however, to develop her views on the situation. In that respect, Virginia’s career did not parallel that of the great feminine nature writer of the 20th century, her friend Rachel Carson. Carson, like Virginia, was a quiet unassuming private person who had worked as an editor and writer for a government agency, had published natural history guide books and nature articles in magazines and was a superb descriptive nature writer. But Carson, whose life was also cut short by disease, managed to make a large statement on the environmental crisis with Silent Spring before she died in 1964. For Virginia Eifert, who was apparently moving in the same direction, the time ran out too soon.

[see one of the letters from Rachel Carson here]

An essay called “Uglification is Aggravation” (March 1966), one of the longest articles she ever wrote for the Living Museum, promotes public awareness of a number of environmental problems; the final chapter of her last book, Of Men and Rivers, also comments on water pollution and the general state of environmental deterioration. But there was time for little else on the subject, except a fine short piece called “Better Than Games” which appeared in the July 1966, issue of the Living Museum. In that essay more forcefully than ever before, Virginia advocated public action to save the wild places:

“The urgent trend is to go back toward our roots. We need to drink at the source, to know the wild places, to learn their truths . . . Yet now, ironically, when we reach out for nature, much of it has gone away from us.

This realization of our great inner need for nature is now a national concern. We must save what is left before there is nothing left to save, before America becomes a parking lot from coast to coast, with cities, cornfields, and trash dumps between.”

The same issue carried a tragic announcement: Virginia Eifert was dead. She had died suddenly on June 16 – after the July issue had been prepared for the press – the victim of a defective heart valve, traceable to her childhood bout with rheumatic fever. She had been to the Mayo Clinic about the problem several years earlier, and so had known that her death would very likely be swift and could come at any time. On the cover of the July issue was one of Virginia’s nature photographs, and it would not have been more symbolic of her lifelong avocation and her central message as the nationally known editor of the Living Museum. It showed an Illinois woods and a beckoning path.

A rare color photo of Virginia in her later years.

John E. Hallwas is associate professor of English at Western Illinois University. He is coeditor of the vision of this land 1976, editor of essays in nature and co editor of Western Illinois regional studies. This feature story appears in the Illinois Times, July 21, 1978.